Arctic wildfires spew soot and smoke cloud bigger than EU

Plume from unprecedented blazes forecast to reach Alaska as fires rage for third month

An aerial view of a wildfire in Boguchar, Russia.

Photograph: Donat Sorokin/Tass

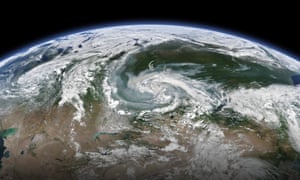

A cloud of smoke and soot bigger than the European Union is billowing across Siberia as wildfires in the Arctic Circle rage into an unprecedented third month.

The normally frozen region, which is a crucial part of the planet’s cooling system, is spewing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and worsening the manmade climate disruption that created the tinderbox conditions.

Quick guide

How global heating is causing more extreme weather

A spate of huge fires in northern Russia, Alaska, Greenland and Canada discharged 50 megatonnes of CO2 in June and 79 megatonnes in July, far exceeding the previous record for the Arctic.

The intensity of the blazes continues with 25 megatonnes in the first 11 days of August – extending the duration beyond even the most persistent fires in the 17-year dataset of Europe’s satellite monitoring system.

Mark Parrington, a scientist in the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, said the previous record was just a few weeks. “We haven’t seen this before,” he said. “The fire intensity is still well above average.”

He said the affected regions previously registered unusually high temperatures and a low level of soil moisture, which created the perfect conditions for ignition. Globally, June and July were the hottest months ever measured.

Russia has suffered most. Last month, the president, Vladimir Putin, mobilised the army to fight the blazes and four Siberian regions declared a state of emergency. But fires continue to rage. The Earth observation scientist Josef Aschbacher said that in Siberia alone, the two-month inferno had destroyed 4.3m hectares of taiga forest.

A Nasa image showing wildfires burning across 11 regions of Russia. Photograph: Nasa Earth Observatory/EPA

The smoke has spread further still. Antti Lipponen, of the Finnish Meteorological Institute, estimates the affected area at 5m square kilometres. “For comparison, the area of EU is about 4.5m km² and the area of contiguous US about 8.1m km²”, he tweeted.

The cloud is billowing north-east and is forecast to reach Alaska, where this year’s fires have already scorched an area bigger than all the wildfires that devastated California last year.

Carly Phillips, of the Union of Concerned Scientists, said Alaskan fires had burned 18.1m acres of forest since 2000, more than double the amount over the previous 20 years.

“Carbon emissions from these wildfires could exacerbate climate warming for decades to come,” she wrote in a blogpost. “Alaska’s ecosystems store huge quantities of carbon both as permafrost and soil that has accumulated over millennia. Wildfires destabilise these stores of carbon by combusting soil and accelerating permafrost thaw, both of which release heat-trapping gases to the atmosphere.”

Wildfires: blazes rage in Arctic during severe heatwave – video

The black soot also settles on what is left of the Arctic ice, weakening its ability to reflect the heat of the sun.

In Greenland, satellite images this month revealed fires stretching across an area 380km wide, adding to the pressures of an Arctic heatwave that caused a record melt-off of the world’s second biggest ice sheet. This week, a huge wildfire in the Qeqqata region left a smouldering area of 6.9km².

Since the start of the year, more than 13.1m hectares have burned, according to Greenpeace, which says this has released as much carbon dioxide as a year’s worth of exhaust fumes from 36m cars.

The Arctic is not the only afflicted region. So far this year, the EU has had 1,600 fires bigger than 30 hectares, which is four times the annual average over the previous decade, according to the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service.

About 1,000 holidaymakers had to evacuate resorts in Gran Canaria this week to escape wildfires. Last month, campers had to abandon their tents due to a fast-spreading blaze in southern France during a heatwave.

In the UK, the Fire Brigades Union says there have been 10% more callouts this year, which has overstretched emergency resources. Firefighter numbers had fallen by a fifth since 2010 due to government cuts, the union said.

As the crisis escalates…

… in our natural world, we refuse to turn away from the climate catastrophe and species extinction. For The Guardian, reporting on the environment is a priority. We give reporting on climate, nature and pollution the prominence it deserves, stories which often go unreported by others in the media. At this pivotal time for our species and our planet, we are determined to inform readers about threats, consequences and solutions based on scientific facts, not political prejudice or business interests.

More people are reading and supporting The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism than ever before. And unlike many news organisations, we have chosen an approach that allows us to keep our journalism accessible to all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford. But we need your ongoing support to keep working as we do.

The Guardian will engage with the most critical issues of our time – from the escalating climate catastrophe to widespread inequality to the influence of big tech on our lives. At a time when factual information is a necessity, we believe that each of us, around the world, deserves access to accurate reporting with integrity at its heart.

Our editorial independence means we set our own agenda and voice our own opinions. Guardian journalism is free from commercial and political bias and not influenced by billionaire owners or shareholders. This means we can give a voice to those less heard, explore where others turn away, and rigorously challenge those in power.

We need your support to keep delivering quality journalism, to maintain our openness and to protect our precious independence. Every reader contribution, big or small, is so valuable. Support The Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Recent Comments