Saving the Whanganui: can personhood rescue a river?

Adam Daniel wades waist deep through the glassy water. Pumice stones spiral in the shallow eddy, while the shrill whistles of a male whio (blue duck) echo upstream through the green canyon walls. The mountain stream’s deep current slows around a lone tree standing on a small rocky island before rushing toward the sea.

Like a doctor, Daniel spends the morning checking the pulse of the river’s upper arteries, taking temperature readings and drawing water samples to diagnose its vitality. Thirty kilometres to his south-east, the Whanganui River’s pristine headwaters begin in the internationally renowned Tongariro National Park, on the western flanks of three cone volcanoes, Ruapehu, Tongariro and Ngauruhoe.

From there the river carves through two national parks, a national forest, farmland, two large towns and many smaller communities on its journey 260km to the south, where it empties into the Tasman Sea.

But the body of water flowing past Daniel is more than a geographical feature. Granted personhood in 2017 by an act of the New Zealand parliament, the Whanganui is the first river in the world to be recognised as an indivisible and living being.

The Māori tribes that live along the Whanganui have always seen the river as sacred – its waters have nourished and blessed the people throughout the 700 years they have lived beside it. The law set in motion new intentions to uphold the mana (prestige) and mauri (life force) of the river.

This river is our river. It is all of ours, and how we look after it belongs to all of us.

Yet despite the river’s new legal status, it still faces challenges from farming and forestry to dams and development. And Daniel – a biologist charged with monitoring river habitat health – is troubled with recent temperature and clarity readings.

The river is sick, and he needs to know where the illness begins.

Defining the river’s rights

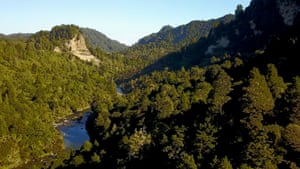

The Whanganui River as seen from a drone. The Māori tribes that live along the waterway have always seen it as sacred. Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

Spring rain cascades down the Ngapuwaiwaha Marae’s decorative roofline in Taumarunui, the first large town the Whanganui River meets. Hundreds gather at 8am to celebrate the river, the new act and the inauguration of the two people selected to speak on behalf of the river: Dame Tariana Turia, an influential Māori political leader, and Turama Hawira, an experienced Māori advisor and educator.

Visitors await the powhiri, a ritual welcoming people to the marae, a fenced-in complex of carved buildings belonging to a particular tribe.

As the rain subsides, Gerrard Albert steps up to the microphone. He is one in a long line of leaders who have fought for recognition of their deep relationship to the river since the 1840 signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding document. He address the crowd in Māori and then in English.

“The settlement legislation recognises Te Awa Tupua as this: a living and indivisible whole comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating its tributaries and all its physical and metaphysical elements,” Albert says. “For the first time, a framework stems from the intrinsic spiritual values of an indigenous belief system.”

When the New Zealand parliament passed the Te Awa Tupua Act granting the Whanganui River system legal personhood, the decision sent waves across the globe, settling the longest water dispute in the nation’s history and establishing a unique legal framework rooted in the Māori worldview of the Whanganui tribes, who revere the river as a tupuna, or ancestor.

The law begins by recognising the river as an indivisible and living being called Te Awa Tupua and outlines four core principles from the tribes’ perspective, including their inalienable connection to the river. Then, it states this being “has all the rights, powers, duties and liabilities of a legal person”.

Tom Barraclough, a legal researcher and expert on the Te Awa Tupua law, says the legislation will give tribes “significant influence” over the future of the river. “As a consequence of giving iwi greater rights, there may be greater protection for nature.”

Dr Erin O’Donnell, a senior fellow at the University of Melbourne law school and author of a book on river rights, agrees. “The act shifts us away from this resource construction where we ask, ‘what do we want from the river?’ and into a space where we can say, ‘what do we want for the river and how do we get there with the river?’”

Over the course of six months, the Guardian travelled the Whanganui to investigate the impact of the new protections – and good intentions.

Moss on a rock along the Whanganui. Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

“You are defining, essentially, the river’s rights,” Albert says.“It puts the river at the centre of the picture and asks us to organise around it.”

This view isn’t unique in the larger legal framework of New Zealand. In 2014, New Zealand gave the same rights to a former national park, Te Urewera, and soon after Mount Taranaki as well.

The trend has also taken hold outside the country. In February 2019, citizens of Toledo, Ohio, granted legal rights to Lake Erie – a fight that began after a 2014 toxic algae bloom shut down city water for three days. India recognised the Ganges and Yamuna rivers as legal entities in 2017, but those rights were overturned. In July 2019, Bangladesh joined suit and granted all of its rivers this same status. And in September the Yurok Tribe in California granted personhood to the Klamath River.

But it’s unclear whether it will work. In the case of Te Awa Tupua, the hard work lies downstream, where the river and its branches encounter development, farming, forestry and run-off which challenge its health and ecology.

Water woes are not unique to the Whanganui River - similar concerns exist across the country. A 600-page Waitangi Tribunal report released last August criticised the government’s Resource Management Act for allowing “a serious degradation of water to occur in many ancestral water bodies”. It highlighted the government’s failure to recognise Māori rights and interests in water. It recommends sweeping changes for both.

Today, those gathered in Taumarunui are celebrating the first step, as the two voices of the river begin meeting with the communities along it to build a strategy that addresses the body of water as an indivisible whole. However, Albert says the law will take years to have an impact.

A fine balance

Despite the Whanganui’s new legal status, it still faces challenges from farming and forestry to dams and development. Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

Near the river’s source at Tongariro National Park, Dave Pickett looks below the surface of the Mangatepopo Stream with a bathyscope. Knee deep in the swift current of this Whanganui tributary, he measures small bugs and algae life clinging to the river bottom, one gauge of a river’s health. He shouts numbers to his colleague.

The men are conducting ecology assessments for Genesis Energy, the company that operates the Tongariro Power Scheme that provides 4% of New Zealand’s energy. The hydropower system diverts the water of the Whanganui River and five of its upper tributaries, including the Mangatepopo. Pickett surveys the stream’s health above and below an intake structure which draws 75% of the water, leaving 25% to flow back into the river. The intake is just outside the park, 15km from the stream’s source and 15km from its confluence with the Whanganui.

The contractors join Campbell Speedy, the environmental coordinator and ecologist working for Genesis. He knows bugs, fish, ecology and the watershed. And he understands the environmental impacts of energy development and the complex cultural landscape of the river.

“This landscape behind us here is Tongariro National Park,” Speedy says. “It’s got dual world heritage status, not only for its volcanic landscape but for its cultural landscape. The water’s coming off a pristine environment. It doesn’t get much better than what we’re seeing right here.”

But like Daniel, Speedy knows the river faces complex issues downstream.

New Zealand’s clean, green image has been mired with reports signalling major water quality issues in many of its rivers. In particular, water quality data from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research shows the lower Whanganui River is often badly contaminated with fecal bacteria and fine sediment from extensive farming on its steep slopes and on the slopes of many of its tributaries.

In addition to these threats, many point the finger at hydropower.

Since the 1970s the power scheme has harnessed energy from these rivers, often leaving the river beds dry below the intakes. In 2004, when Genesis was granted rights to use this water for 35 more years, it came with stipulations requiring the company to keep a certain amount of water in the Whanganui and Mangatepopo. The minimum flows were set to a level to maximise whio food production and food access. Speedy says this aimed to improve the ecology of the Mangatepopo stream and the Whanganui River – leading to healthy levels of bugs and algae, and a water level optimal for the ducks to thrive.

These methods and serious predator eradication programs are working. Speedy says 500 of New Zealand’s 3,000 blue ducks are in this watershed, four times more than in 2001.

Canoeing on the river. Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

Yet the scheme’s viability depends on water. The power company takes only 7% of the entire Whanganui River, but it’s the clearest, cleanest, coldest water at the head. That water is pushed through tunnels, canals, lakes and power stations until it eventually flows into an entirely different river system. On average, only 20% of the Whanganui’s headwaters flow past the intake structure to the sea.

To the tribes that hold this river sacred, this causes environmental, cultural and spiritual damage. They categorically oppose the extraction of their river’s water, and though the new law gives the river newfound rights, it does not reverse pre-existing laws, including the consent granting Genesis the rights to divert water for hydroelectric power until 2039.

Speedy walks across a massive diversion culvert carrying water from the upper tributaries to the power station. He looks down at the narrow Whanganui River below.

“The energy in this river … can be used for electricity, but it also energises the cultural and spiritual values of this landscape, [which is] very important to Māori,” he says. “It energises biodiversity, in the form of animals and fish, like whio and eels, angling for trout fishermen, kayaking, rafting.”

But it is a delicate balance for the country of nearly 5 million people.

“There’s a whole lot of uses from this energy that’s flowing past us here,” Speedy says. “And it’s important to strike that balance between renewable energy to run our society and our economy, but not wreck the environments that we take the energy from.”

‘More dirt than there should be’

‘The turbidity in the river is really high,’ Adam Daniel says. ‘There’s more dirt than there should be.’ Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

Thirty kilometres downriver, Adam Daniel, who works for Fish & Game New Zealand, ploughs through a narrow tunnel of sopping wet ferns and gorse with his quad bike. He checks the GPS and navigates deeper into the steep undulating bush country of the 20,000-hectare Tongariro Forest Conservation Area.

Daniel is on a multi-day adventure collecting water samples on the Whanganui’s upper tributaries. He is using money raised from increased foreign angler licences and Genesis Energy funding intended to mitigate some of its environmental impacts to conduct a two-year water quality study on the upper river.

Previous studies alerted Daniel that the Whanganui River is far dirtier than its tributary the Whakapapa River, even though they both start in the national park. So every month – rain, shine or snow – he visits 16 backcountry study areas to gather water samples and log electro-conductivity and temperature readings.

“We’ve recognised the turbidity in the river is really high – there’s more dirt than there should be,” says Daniel, whose job is to protect river habitat. “So I am trying to identify the catchments [watersheds] here in the upper end of the Whanganui that have high loads of sediment.”

More than halfway through his study, Daniel became alarmed. He was in the back-country preparing to drift down the upper river in a wetsuit to count fish. He waded into the river and looked down.

The energy in this river … also energises the cultural and spiritual values of this landscape.

The Whanganui River had less than a metre visibility (the neighbouring Whakapapa River still had seven metres of visibility).

Daniel hiked every stream on the upper river – they were clear. However, when he checked the stream below the large discharge pipe from Lake Otamangakau, the picture became clearer.

Genesis Energy diverts 80% of Whanganui’s headwaters into the Lake Otamangaka. During low flows in summer, up to three cubic metres of cool water is discharged from the lake. Those flows are intended to help trout, whio and other species during stressful hot weather, but Daniel is concerned it may not be working as intended.

“They can take nearly the entire river of crystal-clear cold water and run it through their man-made lake to keep fish alive, then dump the mixed water with algae and sediment back in the river,” Daniel says.

This drastic change in visibility, coupled with higher water temperatures, has major impacts on the river’s downstream habitat and the non-native trout and other native fish that rely on cold, clean water to thrive in the critical hot and dry summer months.

“We are arguing that their consent condition does not exempt them from the temperature change and that the discharge is clearly having an impact on the river, so they should stop,” Daniel says.

Nigel Clarke, the executive general manager of wholesale operations at Genesis, says the company is compliant with the regulations. “Genesis is committed to the principle of kaitiakitanga; water is essential to our country, our business and to the communities we operate in.

“In complex locations like the Tongariro Power Scheme where there are multiple users of water, we work closely in partnership with local iwi and local communities to positively influence and improve the ecological health and mauri of our waterways.

“Genesis operates the Tongariro Power Scheme in line with resource consents and always welcomes the opportunity to better understand any potential effects of its operations.”

Speedymaintains the turbidity “is not massive … there is some discolouration. It’s not crystal clear but it’s not real dirty brown either.”

But he says Genesis is looking into the issue. “We are going to implement a regime this summer where we do more sampling, where we try and tease out the difference between the various components of the turbidity.”

‘The river is our playground, the river is our work’

The Whanganui has ‘always been a part of us’, Josephine Haworth says. ‘It always will be, until the day we die.’ Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

Some 145km downstream, Josephine Haworth and her husband operate Whanganui River Adventures. They live in Pipiriki, a small village 85km from the sea. The town is nestled in the lush green hills on a curved bend in the river at the southern edge of Whanganui National Park – home to the famous Whanganui Journey, a five-day, 145km canoe trip through the park. Haworth is from the Whanganui tribes and is the third generation of her family to operate a tour business on the river. Her husband grew up here and his family has been in the business since the 1970s.

“The river is nothing new,” Haworth says about the river that runs through her backyard. “It’s always been a part of us. It always will be, until the day we die.”

But the river here is often the colour of chocolate milk from the myriad tributaries that swell with rain and carry soil and sediment from the forest and farm country. The streams bring water, but they also bring sediment and E coli. That’s a concern for the about 18,000 people who canoe it each year. The Haworths lives are intertwined with the river, so it concerns her too.

It’s always been a big part of our lives growing up. The river has always been us.

When it comes to the river’s personhood, she says it’s hard to explain because the river has always been a big part of her family’s lives. “The river is our food source, the river is our playground, the river is our work. It’s always been a big part of our lives growing up. The river has always been us.”

A place to grow

A canoe on the river, areas of which are home to kayaking, rowing and clubs for waka ama, traditional outrigger canoes. Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

In the town of Whanganui near the river’s mouth, Howard Hyland hosed thick mud off the cement boat ramp connecting the Whanganui River Outrigger Canoe Club’s boathouse to the river. The 76-year-old New Zealander is a national coach and paddler for waka ama, traditional outrigger canoes.

Here, near the sea, the river is wide, slow and steady – home to kayaking, rowing and waka ama clubs. Hyland returned from Whakatane to his roots on the river to start a waka ama club for youth.

“I wanted to start a club that was for all peoples, not just for Māori, not just for pākehā, not just for islanders. I wanted it for all of Whanganui,” he says.

Hyland is connected to the river through his grandmother. When he was four years old, he learned to paddle the waka while she fished. Through her love of the river, he became involved in the river and the sport.

A paddler calls out “hup”, signalling the paddlers to switch sides in unison as the team paddle up the river past Hyland. Hyland sees the macro and micro problems the river faces. The biggest issue, he says, is the siphoning of the headwaters for power, but he also details the simple problem of polluting.

“You watch these kids, you see they bring back all the plastics that they see on the river,” Hyland says with a hint of pride. “It tells you they have learned something while they’ve been here. They understand we’ve got to stop polluting the river.”

For Hyland, the river is a vehicle to train good paddlers and good people who care for the river. The river provides his rowers with a place to succeed, a place to grow and a place to find solace at 5:30am as the sun casts first light across the river’s mist.

While the paddlers disappear up river, Howard shares the whakatauki, or philosophy, shared by those connected to the river.

If you give the river a voice, are you going to listen?

About 18,000 people canoe on the river each year. Photograph: Jeremy Lugio/The Guardian

This river is now Te Awa Tupua. The new status offers New Zealand a framework to chart a new course to protect the Whanganui River and provide the world with a blueprint for caring for the earth’s arteries.

Barraclough says there are now guardians who can argue for the river in court, if its rights are infringed. The law doesn’t offer iron-clad protections, but “it does mean that it stands a better chance.”

O’Donnell agrees. “It definitely has power to drive long-term change. How it holds people to account, I think that is going to be the tricky part.”

Hosing off the last mud from the ramp, Hyland wonders what the future will bring for his beloved river. “If you give the river a voice, are you going to listen?”

Comments

(task) Saving the Whanganui: can personhood rescue a river? |...

Zealander and we have seen it on previous visits. Never had time to canoe

it though.

style='FONT-SIZE: small; TEXT-DECORATION: none; FONT-FAMILY: "Calibri"; FONT-WEIGHT: normal; COLOR: #000000; FONT-STYLE: normal; DISPLAY: inline'>

Management - Global

personhood rescue a river? | World news | The Guardian

style='FONT-SIZE: small; TEXT-DECORATION: none; FONT-FAMILY: "Calibri"; FONT-WEIGHT: normal; COLOR: #000000; FONT-STYLE: normal; DISPLAY: inline'>

4 class=Apple-tab-span style="WHITE-SPACE: pre">cover

personhood rights,. river, energy, ecosystem

--

Full

post:

https://resiliencesystem.org/task-saving-whanganui-can-personhood-rescue-river-world-news-guardian

Manage

my subscriptions: https://resiliencesystem.org/mailinglist

Stop emails for

this post:

https://resiliencesystem.org/mailinglist/unsubscribe/14768